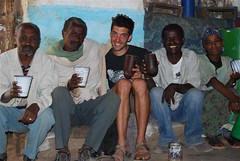

This is me drinking some local tala with farmer friends. Tala is a beer of sorts made from sorghum, millet, sprouted barley, and gesho (a native plants which aid in fermentatin).

Many farmers make tala in their house and grow specific varieties of barley or finger millet that is best for brewing.

Local alcohol seems to be an essential part of life around the world. Tala is the best Ive tried yet - the process is difficult, but is sure is cheap and tasty!

Read More......

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Quick Update!

Hello from Canada!

Many of you are probably surprised Im in Canada- and I will explain later. Aside from some culture shock and exhausting travel - I am enjoying my time here meeting with seed savers, attending seedy saturdays, and exploring a life drastically different from where Ive been.

I have loaded all my Ethiopia Pictures onto flickr and roughly organized them.

Visit this link to view them by sets

http://www.flickr.com/photos/27641699@N08/sets/

or go to this link to view all

http://www.flickr.com/photos/27641699@N08/

Im sorry there are so many pics. Hopefully soon I will pick the best and feature them somehow.

Also, soon I hope to type a summary of my Ethiopian extravaganza. It was a month filled with crop diversity, cultural diversity, passionate farmers, skipping with children, some vomiting, and plenty of good laughs with fellow seed savers. I was challenged on many levels, but left the country even more motivated, inspired, and hopeful than when I arrived. My travels and time with farmers and organizers in Ethiopia confirmed many of my conclusions Ive begun to make and brought them to the next level.

All year I have been pondering the deep connections between culture and crop diversity. Each region Ive been to has shown me how crucial it is to protect and develop the tradtional knowledge associated with these crop varieties. In many ways we are doing an excellent job collecting and storing seeds for later research and use (email me if you want any information about gene banks). However, I have become incredibly passionate about the need to keep these seeds a part of the cultures they are linked to. Through my 120 plus interviews and 8 months of travels I have seen that diversity in crops is directly linked with health and diversity of human cultures. The crops and their resilient seeds have co-evolved with the cultures and eco-systems of their respective regions. It appears to me that the traditional dishes which farmers (women) prepare for ssustenance are directly linked not only to balanced nutrition, but also what can grow well in their region with little inputs!

There is a critical link between nature and culture. When we lose crop varieties from a region - this is not just a biological loss, but a loss of cultural systems, human livelihood, and farmers freedom. We lose not just an inventory of plant materials or genes, but an incredible storehouse of knowledge of how to grow and use the plants. This cultural knowledge which has been developed and adapted over thousands of years is crucial to our survival in the future, especially with climate change looming. The worlds traditional farmers (who have stayed resilient to monoculture and a specific western view of development) hold the key not only to impressive plants and cool seeds - but the diverse knowledge which goes along with these seeds. This knowledge comes as a result of generations of men and women experimenting, selecting crops for their diverse needs, building on the knoweledge on their forefathers, and passing the skils to their children. Each farming family has diverse criteria they use each day to determine how to spread their risk, produce enough food on marginal conditions, and satisfy local demand for alcohol, tasty food, fast cooking, etc. The diverse criteria produces a broad range of crop diversity and an infinite amount of knowlege on local agricultural systems.

Nowhere during this year have farmers been saving seeds and crop diversity solely for economic purposes. Yes, the seeds require much less input and less money than modern high input varieties. However, they are also always tied to complex social, religious, and cultural systems. Ethiopia brought this issue to the forefront of my mind as I watched many traditional dances, took part in coffe ceremonies, tried to learn a local song about teff, and observed the beauty of these rural villages.

We cannot succesfully preserve the genetic diversity of crops withouth preserving the local knowledge and culture which surrounds these crops - how they are planted, saved, stored, cooked, etc.

Ethiopian farmers blew me away traditional agricultural practices and complex local seed systems. In a country where nearly 90% of the population are farmers, agriculture is the central part of life. Much of the science world has disregarded farmers knowledge as "backwards," "traditional" or simply "worthless." This approach confuses me to no end. The power of farmers ancient knowledge can be seen quite evidently in an Ethiopian highland field with its extremely infertile, dry rocky soil that is filled with a diversity of colorful crops satisfying families nutritional, economic, gastronomic, alcoholic, and spiritual needs. In the USA we are trained to see the soil of the Ethiopian highlands and say it is too dry, infertile or not arable. However, farmers have grown on these lands for thousands of years with little inputs. The farmers are usually able to produce an abundance of food on small plots of land - which is highly nutritious, used in various local alcohols, sold in the market, prepared in ceremonies, annd much more.

Even during massive droughts, erosion, and climactic chaos farmers have adapted their systems and their crops to deal with these challeneges. Varieties are continually selected for their ability to withstand extreme drought and weather changes. Farmers plant a diversity of crops and varieties over a range of soil and/or climactic conditions. The farmers spread their risk through an intricate system of seed selection, saving, exchange, and even experimentation. The farmers continue to grow and protect this diversity as a risk prevention strategy. Many tried the new hybrid varieties and saw they couldnt fit in to their system - they yield less in stressed conditions, produce poor straw for the animals, and dont grow well in mixed crop systems. Many women also raved to me about the excellent taste of their special variety in various cultural dishes and insisted on preparing these incredible meals for me (new varieties were often criticized for their taste or long cooking time). Even in the most extreme area of drought and hunger - people still value taste, nutrition, cultural dishes, ceremonial food prepartions, and the diverse values of their food crops.

Ethiopia showed me once again how important diversity and seed saving is not just for survival, but also for community sufficiency and the enjoyment of life.

A major lesson I took from Ethiopia, which I will expound on more later, is the importance of linking the formal and informal seed sectors. Ethiopia is known around the world for the sucess it has had in linking its formal National Gene Bank with many local community seed banks and in-situ conservation in farmers fields. I got to spend time with Dr. Melaku Worede, the founder of the national gene bank, Seeds of Survival, and much more. Dr. Melaku first pushed the idea of the importance of incorporating farmers into "genetic diversity conservation". For years he was ridiculed in the science community and accused of going backwards or being too idealistic. However, his ideas have now enetered the main stream and thousands around the world are learning from Ethiopias system of community seed banks. The Ethiopian government now supprts much of Dr. Melaku's work and is beginning to promote community seed banks throughout the country. Farmers have finally been recognized as essential to preserving diversity in the fields. Seeds have been sucessfully reintroduced and multiplied from the gene bank and even from other gene banks abroad.

No one in the Ethiopian Seed movement is saying we must keep these traditional crops static. The seeds of landraces are collected and stored in secure facilites. However, scientists from NGO's and the National Gene Bank have been working collaboratively with farmers to select and improve varieties to meet farmers diverse needs. The knowledge of many farmers is recorded and then is enhanced with modern scientific knowledge of plant selection and breeding. These efforts have been called "Participatory Plant Breeding" or "Participaty Variety Selection." I promise I will write more on these incredible efforts soon. One amazaing group, Ethio-Organic Seed Actionh (EOSA) is behind much of this work in recent years. They are currently developing a model community seed bank, enhancing landrace varietes, and training many farmers around the coutnry. Their work is focused on protecting Ethiopias incredible agricultural heritage while slightly enhancing it with modern techniques.

Anyway, it is late now and I have rambled for long enough. For the time being I have given up on organized blog entries and will continue to post these incoherent rants. Keep checking for some more succint, sane posts in the future. I cant explain why I am in this strange writers block. Perhaps it is because of my culture shock here in Canada (I have so many questions constantly circulating in my mind as I try to apply all the lessons Ive learned to the seed saving scene here).

My mind is filled with concrete answers, but also concrete questions which have no one answer. I want to somehow download all Ive seen and felt to all of you - but it is impossible. Even the pictures to not do it justice. Hopefully, I will find a way to give you all a taste of this ridiculous journey and research

A big thanks to all the farmers of Ethiopia who taught me so much. They continue to protect an immense amount of seeds and knowledge which are crucial to our survival. I cant say thank them enough for all the hope, ideas, delicious meals, and seeds they have bestowed upon me. Read More......

Many of you are probably surprised Im in Canada- and I will explain later. Aside from some culture shock and exhausting travel - I am enjoying my time here meeting with seed savers, attending seedy saturdays, and exploring a life drastically different from where Ive been.

I have loaded all my Ethiopia Pictures onto flickr and roughly organized them.

Visit this link to view them by sets

http://www.flickr.com/photos/27641699@N08/sets/

or go to this link to view all

http://www.flickr.com/photos/27641699@N08/

Im sorry there are so many pics. Hopefully soon I will pick the best and feature them somehow.

Also, soon I hope to type a summary of my Ethiopian extravaganza. It was a month filled with crop diversity, cultural diversity, passionate farmers, skipping with children, some vomiting, and plenty of good laughs with fellow seed savers. I was challenged on many levels, but left the country even more motivated, inspired, and hopeful than when I arrived. My travels and time with farmers and organizers in Ethiopia confirmed many of my conclusions Ive begun to make and brought them to the next level.

All year I have been pondering the deep connections between culture and crop diversity. Each region Ive been to has shown me how crucial it is to protect and develop the tradtional knowledge associated with these crop varieties. In many ways we are doing an excellent job collecting and storing seeds for later research and use (email me if you want any information about gene banks). However, I have become incredibly passionate about the need to keep these seeds a part of the cultures they are linked to. Through my 120 plus interviews and 8 months of travels I have seen that diversity in crops is directly linked with health and diversity of human cultures. The crops and their resilient seeds have co-evolved with the cultures and eco-systems of their respective regions. It appears to me that the traditional dishes which farmers (women) prepare for ssustenance are directly linked not only to balanced nutrition, but also what can grow well in their region with little inputs!

There is a critical link between nature and culture. When we lose crop varieties from a region - this is not just a biological loss, but a loss of cultural systems, human livelihood, and farmers freedom. We lose not just an inventory of plant materials or genes, but an incredible storehouse of knowledge of how to grow and use the plants. This cultural knowledge which has been developed and adapted over thousands of years is crucial to our survival in the future, especially with climate change looming. The worlds traditional farmers (who have stayed resilient to monoculture and a specific western view of development) hold the key not only to impressive plants and cool seeds - but the diverse knowledge which goes along with these seeds. This knowledge comes as a result of generations of men and women experimenting, selecting crops for their diverse needs, building on the knoweledge on their forefathers, and passing the skils to their children. Each farming family has diverse criteria they use each day to determine how to spread their risk, produce enough food on marginal conditions, and satisfy local demand for alcohol, tasty food, fast cooking, etc. The diverse criteria produces a broad range of crop diversity and an infinite amount of knowlege on local agricultural systems.

Nowhere during this year have farmers been saving seeds and crop diversity solely for economic purposes. Yes, the seeds require much less input and less money than modern high input varieties. However, they are also always tied to complex social, religious, and cultural systems. Ethiopia brought this issue to the forefront of my mind as I watched many traditional dances, took part in coffe ceremonies, tried to learn a local song about teff, and observed the beauty of these rural villages.

We cannot succesfully preserve the genetic diversity of crops withouth preserving the local knowledge and culture which surrounds these crops - how they are planted, saved, stored, cooked, etc.

Ethiopian farmers blew me away traditional agricultural practices and complex local seed systems. In a country where nearly 90% of the population are farmers, agriculture is the central part of life. Much of the science world has disregarded farmers knowledge as "backwards," "traditional" or simply "worthless." This approach confuses me to no end. The power of farmers ancient knowledge can be seen quite evidently in an Ethiopian highland field with its extremely infertile, dry rocky soil that is filled with a diversity of colorful crops satisfying families nutritional, economic, gastronomic, alcoholic, and spiritual needs. In the USA we are trained to see the soil of the Ethiopian highlands and say it is too dry, infertile or not arable. However, farmers have grown on these lands for thousands of years with little inputs. The farmers are usually able to produce an abundance of food on small plots of land - which is highly nutritious, used in various local alcohols, sold in the market, prepared in ceremonies, annd much more.

Even during massive droughts, erosion, and climactic chaos farmers have adapted their systems and their crops to deal with these challeneges. Varieties are continually selected for their ability to withstand extreme drought and weather changes. Farmers plant a diversity of crops and varieties over a range of soil and/or climactic conditions. The farmers spread their risk through an intricate system of seed selection, saving, exchange, and even experimentation. The farmers continue to grow and protect this diversity as a risk prevention strategy. Many tried the new hybrid varieties and saw they couldnt fit in to their system - they yield less in stressed conditions, produce poor straw for the animals, and dont grow well in mixed crop systems. Many women also raved to me about the excellent taste of their special variety in various cultural dishes and insisted on preparing these incredible meals for me (new varieties were often criticized for their taste or long cooking time). Even in the most extreme area of drought and hunger - people still value taste, nutrition, cultural dishes, ceremonial food prepartions, and the diverse values of their food crops.

Ethiopia showed me once again how important diversity and seed saving is not just for survival, but also for community sufficiency and the enjoyment of life.

A major lesson I took from Ethiopia, which I will expound on more later, is the importance of linking the formal and informal seed sectors. Ethiopia is known around the world for the sucess it has had in linking its formal National Gene Bank with many local community seed banks and in-situ conservation in farmers fields. I got to spend time with Dr. Melaku Worede, the founder of the national gene bank, Seeds of Survival, and much more. Dr. Melaku first pushed the idea of the importance of incorporating farmers into "genetic diversity conservation". For years he was ridiculed in the science community and accused of going backwards or being too idealistic. However, his ideas have now enetered the main stream and thousands around the world are learning from Ethiopias system of community seed banks. The Ethiopian government now supprts much of Dr. Melaku's work and is beginning to promote community seed banks throughout the country. Farmers have finally been recognized as essential to preserving diversity in the fields. Seeds have been sucessfully reintroduced and multiplied from the gene bank and even from other gene banks abroad.

No one in the Ethiopian Seed movement is saying we must keep these traditional crops static. The seeds of landraces are collected and stored in secure facilites. However, scientists from NGO's and the National Gene Bank have been working collaboratively with farmers to select and improve varieties to meet farmers diverse needs. The knowledge of many farmers is recorded and then is enhanced with modern scientific knowledge of plant selection and breeding. These efforts have been called "Participatory Plant Breeding" or "Participaty Variety Selection." I promise I will write more on these incredible efforts soon. One amazaing group, Ethio-Organic Seed Actionh (EOSA) is behind much of this work in recent years. They are currently developing a model community seed bank, enhancing landrace varietes, and training many farmers around the coutnry. Their work is focused on protecting Ethiopias incredible agricultural heritage while slightly enhancing it with modern techniques.

Anyway, it is late now and I have rambled for long enough. For the time being I have given up on organized blog entries and will continue to post these incoherent rants. Keep checking for some more succint, sane posts in the future. I cant explain why I am in this strange writers block. Perhaps it is because of my culture shock here in Canada (I have so many questions constantly circulating in my mind as I try to apply all the lessons Ive learned to the seed saving scene here).

My mind is filled with concrete answers, but also concrete questions which have no one answer. I want to somehow download all Ive seen and felt to all of you - but it is impossible. Even the pictures to not do it justice. Hopefully, I will find a way to give you all a taste of this ridiculous journey and research

A big thanks to all the farmers of Ethiopia who taught me so much. They continue to protect an immense amount of seeds and knowledge which are crucial to our survival. I cant say thank them enough for all the hope, ideas, delicious meals, and seeds they have bestowed upon me. Read More......

Ethiopia Update – First Weeks

God I could tell you so much!!

I had no idea how ancient, magical, and culturally rich Ethiopia was. I came here because of its diverse crops and have in turn learned so much more about their farming techniques, village systems, seed sharing and exchange, ancient Christianity, wonderful food, song and dance, and their overall attitude toward life.

I don’t have time or composure to write it all now, so hopefully we will meet later and have time to talk and for me to show you my pictures so far. I first want to say that nobody is starving here right now (well maybe a few beggars, but there are beggars in NYC too) and there is no war. The famine was a result of droughts which were caused partly by massive deforestation. The famines were worsened by war and corrupt leaders. Now, there is a drought but the harvest season just ended so most farmers have enough food. Nearly 90% of the country is farmers. The farming and rural culture is so ancient here. They are still farming in a very similar way to how the common man farmed and lived here at least 500 years before Christ (cave paintings and clay sculptures depict plows, seeds, and techniques that are still used today).

Seeds have a deep spiritual and cultural value here. When I asked one farmer where his seeds first came from he responded by saying, "What do you mean? I know where I came from. I came from my parents and their parents as well, all the way back to god. My seeds came as a gift from my father when he died and his father did the same for him. Ultimately the seeds are a gift from god and connect me with my family and our entire history."

This farmer (Weldu) and his family has been the highlight of my time so far. I spent four hours with them and my friendly guide/ translator (the local agricultural coordinator). Weldu and his wife took down their giant pots and for hours taught me about their seeds and all the associated stories and techniques. The pots they store the seeds in are handmade from clay and dung. They smoke the pots with burning hot peppers and goat dung to protect from insects. They make a concoction from 6 local plants to coat the seeds and further protect them. Thy excitedly showed me over 22 varieties of wheat, sorghum, barley, fava bean, chickpea, teff (the local grain and staple crop of Ethiopia), etc. They have varieties for every weather condition and soil type. There is an incredibly complex system of how to intercrop and manage each crop. Each crop also has a story and a special way of preparing.

With laughter filling the room - his wife made numerous cultural dishes and drinks for me (popped sorghum, injeera with wet, and tala (local beer from millet, barley, sorghum, and gesho).

One sorghum variety was named "the one which saved grandma"(when translated) because it was the only crop which survived the drought in 1970’s and helped to save the family from starvation. Other varieties where named because of the Priest who gave them, the meal they are used for, a certain nutritional value, texture, shape, or the type of soil they grow in. Weldu, like all Ethiopian farmers I have met, spreads out his risk by planting a diversity of crops and varieties over various soil types and conditions. The farmers know all details of each variety and use a complex system to determine which crops or types to grow depending on the grain, the quality of the soil in that area, or the predicted needs of the family.

There is so much more I could write on this topic. Like in India, Seed Saving and growing a diversity of crops is not a choice or fun hobby for farmers here. Many farmers were baffled when I asked why they grow such a diversity of crops. Without a knowledge of the corporate system and worldwide agricultural crisis, they explained to me how they would die if they ever grew a monoculture. The diverse crops are grown as a risk prevention strategy. However, the farmers also explained to me the various cultural uses of the crops. Some barley is used for flat breads, while others are used for making tala (a local beer). Certain sorghum is good for Injeera while others are good for porridge. White Teff produces less, but it is highly prized and farmers grow it to sell in market. Red Teff produces more on marginal soils, and farmers like the taste and nutrition better, but don’t sell in market. Flax is grown on areas with poor soil conditions. Pulses like fava beans or lentils (depending on the region) or used in crop rotation when farmers see the soil needs improvement. Teff is grown in soils that flood. Finger Millet and Sorghum is planted if the rains come early while faster growing crops like Teff are planted if the rain comes late. Fields for Teff are plowed 4 times, while wheat fields are usually plowed 2-3 times. Animals are walked over the fled after teff is broadcast to ensure its contact with the soil and discourage birds from eating the seed. “Hamfas” is a system of intercropping wheat and barley – the varieties for this system are special and have been selected over many years. These fields give higher yields and are the harvest is mixed together and milled for certain local breads. A special variety of wheat is grown for bread used in the church during certain festivals. These are just a few of the agricultural/ seed techniques I remember off the top of my head.

I will write more later about Farmers traditional knowledge/ methods. Email me if you have specific questions!

Today I generally feel very good. But, I have concluded that I could never be a rock star. It is exhausting being mobbed by children and people at every turn. In the rural areas the children swarm me just to look, laugh, and touch me. My guide translated and told me I was the first white person they had seen. They were asking "How I lost my color and why I looked so funny".

The town where I stayed for the past few days here is a tourist center because of its ancient churches, temples, and tombs. The Aksumite civilization thrived here from the 4th century BC to the 7th Century AD (these dates are heavily debated). It is believed that Christianity reached here just one month after Jesus Died. And there is a special building here which houses the "Ark of the covenant" - the rock with the Ten Commandments written on them. Only one monk lives and guards the ark for his entire life. When he dies another one is chosen. Nobody else can see the Ark. The churches are cool, but the tourists piss me off and around the town I am constantly swarmed by children begging for money or sweets. They all have the same act - they make a sad face and say their parents have died or they are starving. The majority of them are lying and just trying to milk the tourists. They are poor, but giving money does not help at all and just furthers a terrible system of reliance on foreign tourists instead of their farms.

I have determined that I don’t really care about seeing old churches or tourist sites much. Instead, I love talking with farmers and wandering crazy markets filled with camels, salt, ancient grains, incredible baskets, etc.

One cool farmer I met today hand dug a well 12 meters down (crazy!!). He would pull himself out each day by a rope of leather, and horse and camel hair. When he finished the well he designed and built a water pump from all spare parts or trash he found (old bike tires, spare car parts, candy wrappers, etc). Now, him and his neighbors have water for their crops and can deal with the drought! They are growing vegetables and fruit to make more income.

Overall, I am amazed not by the poverty, but by the joy here. Some rich Italian tourists I talked today told me all they notice is the barefoot children and flies on their faces. What I really notice is the constant laughter and smiles on children’s faces as we skip through the fields together. Also, I really notice the deep laughter in the old women’s guts as they show me their seeds.

Here is a quote from the book “Shattering: Food Politics and the Loss of genetic Diversity” by Pat Mooney and Cary Fowler about Ethiopians Seeds – very similar conclusions to my experiences

"Back in the early 1970s, a scientist from Purdue University made the journey to Ethiopia to gather sorghum. Some years later, we were told that he forwarded a copy of his laboratory analysis of the farmer cultivars to his Ethiopian hosts. According to the report, he had 'discovered' that one sorghum accession had very high protein content and excellent baking qualities. He could have saved himself some laboratory time had it occurred to him to ask the farmer who first gave him the seed about its characteristics. Ethiopians call their variety sinde lemine, which translates as 'why bother with wheat?'

"When Yilma Kebede tells the story, he literally shakes with laughter. Lounging with one leg stretched out on an office sofa, Dr. Yilma talks of another high-lysine sorghum, the name for which is 'milk in my cheeks.' As team leader for sorghum breeding at the research institute in Nazret, Yilma has developed a healthy respect for Ethiopian farmers and their contribution to sorghum. His natural easy-going style left him though, when he recalled an earlier visit from Ciba-Geigy officials who tried to sell hybrid grain sorghum to his government. 'It is ours,' he told us. 'Sorghum originated here in Ethiopia .'

Across the room, Yilma's colleague, Dr. Melaku Worede, shares both his irritation and his solutions. Melaku is charged with one of the toughest and most important jobs in the world. He is the director of the Plant Genetic Resources Center , the genetic conservation campaign for Ethiopia .

"In and of itself Ethiopia could be regarded as a Vavilov center. Its fantastic terrain of mountains, valleys and plateaus, combined with a long history of cultivation, make the country one of the most botanically diverse and important points on the globe. Ethiopia is home to major world crops like sorghum and many millets, as well as coffee. Less well-known outside the country is its teff crop, which is still the most important food staple. Thousands of years of farming have made the region a secondary center of diversity for wheat and barley as well.

"But Melaku Worede stresses that his country's ragged landscape is only part of the story. The other part is its people. 'A farmer will take me to his bin and I will look in at the barley or teff or sorghum and I will see nothing. To me, it looks the same.' Melaku waves his arm. 'But the farmer will just reach in and show me that this one is for this soil and this one is for that and this one makes good injura [Ethiopian bread made with fermented dough] and so on. I am the scientist with the training. But farmer knows his seed.' " Read More......

I had no idea how ancient, magical, and culturally rich Ethiopia was. I came here because of its diverse crops and have in turn learned so much more about their farming techniques, village systems, seed sharing and exchange, ancient Christianity, wonderful food, song and dance, and their overall attitude toward life.

I don’t have time or composure to write it all now, so hopefully we will meet later and have time to talk and for me to show you my pictures so far. I first want to say that nobody is starving here right now (well maybe a few beggars, but there are beggars in NYC too) and there is no war. The famine was a result of droughts which were caused partly by massive deforestation. The famines were worsened by war and corrupt leaders. Now, there is a drought but the harvest season just ended so most farmers have enough food. Nearly 90% of the country is farmers. The farming and rural culture is so ancient here. They are still farming in a very similar way to how the common man farmed and lived here at least 500 years before Christ (cave paintings and clay sculptures depict plows, seeds, and techniques that are still used today).

Seeds have a deep spiritual and cultural value here. When I asked one farmer where his seeds first came from he responded by saying, "What do you mean? I know where I came from. I came from my parents and their parents as well, all the way back to god. My seeds came as a gift from my father when he died and his father did the same for him. Ultimately the seeds are a gift from god and connect me with my family and our entire history."

This farmer (Weldu) and his family has been the highlight of my time so far. I spent four hours with them and my friendly guide/ translator (the local agricultural coordinator). Weldu and his wife took down their giant pots and for hours taught me about their seeds and all the associated stories and techniques. The pots they store the seeds in are handmade from clay and dung. They smoke the pots with burning hot peppers and goat dung to protect from insects. They make a concoction from 6 local plants to coat the seeds and further protect them. Thy excitedly showed me over 22 varieties of wheat, sorghum, barley, fava bean, chickpea, teff (the local grain and staple crop of Ethiopia), etc. They have varieties for every weather condition and soil type. There is an incredibly complex system of how to intercrop and manage each crop. Each crop also has a story and a special way of preparing.

With laughter filling the room - his wife made numerous cultural dishes and drinks for me (popped sorghum, injeera with wet, and tala (local beer from millet, barley, sorghum, and gesho).

One sorghum variety was named "the one which saved grandma"(when translated) because it was the only crop which survived the drought in 1970’s and helped to save the family from starvation. Other varieties where named because of the Priest who gave them, the meal they are used for, a certain nutritional value, texture, shape, or the type of soil they grow in. Weldu, like all Ethiopian farmers I have met, spreads out his risk by planting a diversity of crops and varieties over various soil types and conditions. The farmers know all details of each variety and use a complex system to determine which crops or types to grow depending on the grain, the quality of the soil in that area, or the predicted needs of the family.

There is so much more I could write on this topic. Like in India, Seed Saving and growing a diversity of crops is not a choice or fun hobby for farmers here. Many farmers were baffled when I asked why they grow such a diversity of crops. Without a knowledge of the corporate system and worldwide agricultural crisis, they explained to me how they would die if they ever grew a monoculture. The diverse crops are grown as a risk prevention strategy. However, the farmers also explained to me the various cultural uses of the crops. Some barley is used for flat breads, while others are used for making tala (a local beer). Certain sorghum is good for Injeera while others are good for porridge. White Teff produces less, but it is highly prized and farmers grow it to sell in market. Red Teff produces more on marginal soils, and farmers like the taste and nutrition better, but don’t sell in market. Flax is grown on areas with poor soil conditions. Pulses like fava beans or lentils (depending on the region) or used in crop rotation when farmers see the soil needs improvement. Teff is grown in soils that flood. Finger Millet and Sorghum is planted if the rains come early while faster growing crops like Teff are planted if the rain comes late. Fields for Teff are plowed 4 times, while wheat fields are usually plowed 2-3 times. Animals are walked over the fled after teff is broadcast to ensure its contact with the soil and discourage birds from eating the seed. “Hamfas” is a system of intercropping wheat and barley – the varieties for this system are special and have been selected over many years. These fields give higher yields and are the harvest is mixed together and milled for certain local breads. A special variety of wheat is grown for bread used in the church during certain festivals. These are just a few of the agricultural/ seed techniques I remember off the top of my head.

I will write more later about Farmers traditional knowledge/ methods. Email me if you have specific questions!

Today I generally feel very good. But, I have concluded that I could never be a rock star. It is exhausting being mobbed by children and people at every turn. In the rural areas the children swarm me just to look, laugh, and touch me. My guide translated and told me I was the first white person they had seen. They were asking "How I lost my color and why I looked so funny".

The town where I stayed for the past few days here is a tourist center because of its ancient churches, temples, and tombs. The Aksumite civilization thrived here from the 4th century BC to the 7th Century AD (these dates are heavily debated). It is believed that Christianity reached here just one month after Jesus Died. And there is a special building here which houses the "Ark of the covenant" - the rock with the Ten Commandments written on them. Only one monk lives and guards the ark for his entire life. When he dies another one is chosen. Nobody else can see the Ark. The churches are cool, but the tourists piss me off and around the town I am constantly swarmed by children begging for money or sweets. They all have the same act - they make a sad face and say their parents have died or they are starving. The majority of them are lying and just trying to milk the tourists. They are poor, but giving money does not help at all and just furthers a terrible system of reliance on foreign tourists instead of their farms.

I have determined that I don’t really care about seeing old churches or tourist sites much. Instead, I love talking with farmers and wandering crazy markets filled with camels, salt, ancient grains, incredible baskets, etc.

One cool farmer I met today hand dug a well 12 meters down (crazy!!). He would pull himself out each day by a rope of leather, and horse and camel hair. When he finished the well he designed and built a water pump from all spare parts or trash he found (old bike tires, spare car parts, candy wrappers, etc). Now, him and his neighbors have water for their crops and can deal with the drought! They are growing vegetables and fruit to make more income.

Overall, I am amazed not by the poverty, but by the joy here. Some rich Italian tourists I talked today told me all they notice is the barefoot children and flies on their faces. What I really notice is the constant laughter and smiles on children’s faces as we skip through the fields together. Also, I really notice the deep laughter in the old women’s guts as they show me their seeds.

Here is a quote from the book “Shattering: Food Politics and the Loss of genetic Diversity” by Pat Mooney and Cary Fowler about Ethiopians Seeds – very similar conclusions to my experiences

"Back in the early 1970s, a scientist from Purdue University made the journey to Ethiopia to gather sorghum. Some years later, we were told that he forwarded a copy of his laboratory analysis of the farmer cultivars to his Ethiopian hosts. According to the report, he had 'discovered' that one sorghum accession had very high protein content and excellent baking qualities. He could have saved himself some laboratory time had it occurred to him to ask the farmer who first gave him the seed about its characteristics. Ethiopians call their variety sinde lemine, which translates as 'why bother with wheat?'

"When Yilma Kebede tells the story, he literally shakes with laughter. Lounging with one leg stretched out on an office sofa, Dr. Yilma talks of another high-lysine sorghum, the name for which is 'milk in my cheeks.' As team leader for sorghum breeding at the research institute in Nazret, Yilma has developed a healthy respect for Ethiopian farmers and their contribution to sorghum. His natural easy-going style left him though, when he recalled an earlier visit from Ciba-Geigy officials who tried to sell hybrid grain sorghum to his government. 'It is ours,' he told us. 'Sorghum originated here in Ethiopia .'

Across the room, Yilma's colleague, Dr. Melaku Worede, shares both his irritation and his solutions. Melaku is charged with one of the toughest and most important jobs in the world. He is the director of the Plant Genetic Resources Center , the genetic conservation campaign for Ethiopia .

"In and of itself Ethiopia could be regarded as a Vavilov center. Its fantastic terrain of mountains, valleys and plateaus, combined with a long history of cultivation, make the country one of the most botanically diverse and important points on the globe. Ethiopia is home to major world crops like sorghum and many millets, as well as coffee. Less well-known outside the country is its teff crop, which is still the most important food staple. Thousands of years of farming have made the region a secondary center of diversity for wheat and barley as well.

"But Melaku Worede stresses that his country's ragged landscape is only part of the story. The other part is its people. 'A farmer will take me to his bin and I will look in at the barley or teff or sorghum and I will see nothing. To me, it looks the same.' Melaku waves his arm. 'But the farmer will just reach in and show me that this one is for this soil and this one is for that and this one makes good injura [Ethiopian bread made with fermented dough] and so on. I am the scientist with the training. But farmer knows his seed.' " Read More......

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Threshing Wheat

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.JPG)